13. Post-Reformation, Revival, the Great Awakening

| Key Dates # |

|

|---|

| 1603 | James I becomes King of England

|

| 1610 | Brother Lawrence born

|

| 1611 | King James Version, the most influential English translation of the Bible

|

| 1620 | Plymouth, Massachusetts colony founded by Puritans

|

| 1625 | Charles I becomes King. He too is against the Puritans

|

| 1628 | Puritan John Bunyan, author of Pilgrim's Progress among other works

|

| 1648 | End of the Thirty Years War; Treaty of Westphalia > the end of chronic

Catholic/Protestant wars that started after the Reformation.

|

| 1658 | Cromwell dies

|

| 1660 | Charles II becomes King of England

|

| 1685 | Birth of JS Bach, one of the greatest composers of all time (died 1750)

|

| Birth of George Frideric Handel, Baroque composer famous for his operas,

oratorios, anthems and organ concertos (died 1759)

|

| 1688 | William & Mary on English throne. Puritans free to preach, establish churches

|

| 1703 | Jonathan Edwards born

|

| 1714 | George Whitefield born

|

| 1718 | David Brainerd, American missionary among indigenous Americans (particularly the

Delaware Indians of New Jersey), born at Haddam, Connecticut (died 1747)

|

| 1727 | Revival among Count Nikolaus Ludwig Zinzendorf and Hussite Moravian refugees

he had taken in. Moravian missionary movement *

|

| 1720s | Beginning of the First Great Awakening

|

| 1734-1737 | The Great Awakening continues as Jonathan Edwards preaches in Massachusetts.

Revival spreads to Connecticut

|

| 1739-41 | George Whitefield joins Edwards. Travelled between England and America 13

times; reached about 80% of the American colonists with the Gospel

|

| 1759 | William Wilberforce, evangelical who fought against slavery, born

|

| 1779 | Olney Hymns produced by John Newton and William Cowper.

|

| 1784 | John Wesley baptizes Thomas Coke, making Methodism a denomination separate

from the Church of England

|

| 1792 | William Carey, "Expect great things from God. Attempt great things for God." *

|

| 1792 | Particular Baptist Society for Propagating the Gospel among the Heathen

founded, later called the Baptist Missionary Society *

|

| 1792 | Charles Finney, forerunner of modern revivalism, born

|

| 1795 | London Missionary Society founded *

|

| 1799 | Church Missionary Society founded *

|

| 1824 | Charles Finney leads revivals in the USA. The Second Great Awakening

|

* The story of Christian missions will be covered later in the semester.

Influential People and Events

Brother Lawrence (1611-1691)

Born Nicholas Herman in France, he served for a period in the army before retiring due to injury.

He then entered the Discalced Carmelite monastery in Paris as Brother Lawrence.

He was assigned to the monastery kitchen where, amidst the tedious chores of cooking and

cleaning at the constant bidding of his superiors, he developed his rule of spirituality and work.

"I began to live as if there were no one save God and me in the world." Brother Lawrence

cooked meals, ran errands, scrubbed pots, and endured the scorn of the world as though in

everything he did he was in the presence of God. "As often as I could, I placed myself as a

worshiper before him, fixing my mind upon his holy presence, recalling it when I found it

wandering from him. This proved to be an exercise frequently painful, yet I persisted through all

difficulties."

For three centuries the writings of Brother Lawrence have taught Christians that God is as

present in the kitchen as in the cathedral/church and as accessible in the living room as He is

around the Lord's Table.

This simple, yet profound teaching has empowered many to seek the joy of God's presence in the

midst of every moment and circumstance.

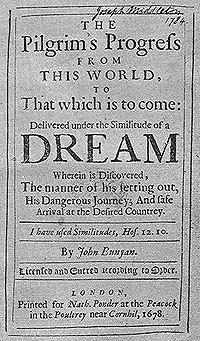

John Bunyan (1628-1688) - "Pilgrim's Progress"

"Pilgrim's Progress

Bunyan in Jail

John Bunyan started out as a tinker (an itinerant tinsmith) and served in the parliamentary army

from 1644 to 1647. He was received into the Baptist church in Bedford by immersion in 1653.

In 1655, Bunyan became a deacon and began preaching. In 1658 he was charged with preaching

without a license. In November 1660 he was taken to the county jail in Silver Street, Bedford,

and confined (with the exception of a few weeks in 1666) for 12 years until January 1672. He

then became pastor of the Bedford church. In March 1675 he was again imprisoned for six

months) for preaching without a license. Bunyan was a forerunner of open air preaching that

enabled him to reach vast numbers of people shut out by ecclesiastical traditions and

intolerance.

Bunyan wrote The Pilgrim's Progress, the most successful allegory ever written. The book is an

allegory of the conflict between religion and society, featuring Bunyan's own spiritual struggle as

he found salvation in Christ and began preaching. He wrote other books, including one which

discussed his inner life and reveals his preparation for his appointed work is Grace Abounding to

the Chief of Sinners (1666).

In theology Bunyan was a Puritan, but not legalistically so.

George Fox (1624-1691) - The Quakers

In the mid 1600s Fox, a shoemaker, began a four year journey throughout England, seeking

answers to spiritual questions he could not find answers to in the established church.

Disappointed with the answers he received from religious leaders, he felt an inner call to

become an itinerant preacher. He frequently ran into trouble when he visited churches and

preached his own messages, sometimes contradicting what the official ministers had said. Fox's

own meetings were radically different from orthodox Christianity: simple premises, silent

meditation, with no music, rituals, or creeds. His movement (which he named "The Friends of

Truth") ran afoul of Oliver Cromwell's Puritan government, as well as that of Charles II, when

the monarchy was restored. Fox's followers, called Friends, refused to pay tithes to the state

church, would not take oaths in court, declined to lift their hats to those in power, rejected the

idea of Christmas and refused to serve in combat during war. Furthermore, they fought for the

end of slavery and more humane treatment of criminals, both unpopular stands at the time.

Once, when hauled before a judge, Fox chided the jurist to "tremble before the word of the

Lord." The judge mocked Fox, calling him a "quaker," and the nickname stuck. Quakers were

persecuted across England, and hundreds died in jails. They fared no better in the American

colonies. Colonists who worshiped in the established Christian denominations considered

Quakers heretics. "Friends" were deported, imprisoned and some were hanged as witches.

Eventually they found a haven in Rhode Island, which decreed religious tolerance. William Penn

(1644-1718), a prominent Quaker, received a large land grant in payment for a debt the crown

owed his family. Penn founded Pennsylvania colony and worked Quaker beliefs into its

government. Quakerism flourished there. Over the years they were accepted and branches were

established in many countries in the world, including Australia. They remain influential.

The Puritans

The Puritans were members of a group of English Protestants who in the 16th and 17th centuries

advocated strict religious discipline along with simplification of the ceremonies and creeds of

the (dominant) Church of England. They lived in accordance with Protestant precepts of the

time, including teaching that regarded pleasure or luxury as sinful.

Puritanism was stern and sombre; it was founded on strict Calvinism; it had a huge overburden

of legalism rather than grace. Christian writers note that the Puritans lived under a covenant of

"works". This was because they had not yet fully grasped the whole truth of divine revelation.

For example, a man might be fined, imprisoned, or whipped for non-attendance at church

services; he would be dealt with still more harshly if he spoke against religion or denied the

divine origin of any book of the Bible. Laws were made that tended to force the conscience, to

curb the freedom of the will, and to suppress the exuberance of youth -- laws that could not

have been enacted and enforced by a people who comprehended the full meaning of the Gospel.

However, their lifestyle needs to be evaluated in the context of their times.

The Puritans worked for religious, moral and social reforms. The strict ideas of John Calvin were

pivotal to their beliefs. The Puritans contended that the Church of England had become a

product of political struggles and man-made doctrines. In the end, they concluded that the

church was beyond reform. Escaping persecution, many Puritans went to America.

In September 1620, a merchant ship called the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth, a port on the

southern coast of England. On this trip the ship carried 102 passengers, all hoping to start a new

life on the other side of the Atlantic. Nearly 40 of these passengers were Protestant Separatists-

they called themselves "Saints"-who hoped to establish a new church in the New World. Today,

we often refer to the colonists who crossed the Atlantic on the Mayflower as "Pilgrims." The

Puritans believed the Bible was God's law, and that it provided a plan for living. The established

church limited access to God to the confines of "church authority". Puritans sought to strip away

traditional trappings and formalities of Christianity that had been slowly building.

In September 1620, a merchant ship called the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth, a port on the

southern coast of England. On this trip the ship carried 102 passengers, all hoping to start a new

life on the other side of the Atlantic. Nearly 40 of these passengers were Protestant Separatists-

they called themselves "Saints"-who hoped to establish a new church in the New World. Today,

we often refer to the colonists who crossed the Atlantic on the Mayflower as "Pilgrims." The

Puritans believed the Bible was God's law, and that it provided a plan for living. The established

church limited access to God to the confines of "church authority". Puritans sought to strip away

traditional trappings and formalities of Christianity that had been slowly building.

The English Civil War (1642-1651)

The English Civil War was a series of conflicts between Parliamentarians and Royalists. The first

(1642-46) and second (1648-49) civil wars pitted the supporters of King Charles I against the

supporters of the Long Parliament, while the third war (1649-51) saw fighting between

supporters of King Charles II and supporters of the Rump Parliament. The Civil War ended with a

Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651.

The Civil War led to the trial and execution of Charles I, the exile of Charles II, and replacement

of the English monarchy with first, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53), and then with a

Protectorate (1653-1659), under the rule of Oliver Cromwell (and, after his death, his son

Richard). The monopoly of the Church of England on Christian worship ended with the victors

consolidating the established Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland.

The wars established the precedent that an English monarch cannot govern without Parliament's

consent, although this concept was legally established only with the Glorious Revolution later in

the century. The Protectorate Parliament was not a success and was dissolved in 1659; the Rump

Parliament was recalled, leading eventually to the restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

Some Christian Leaders During this Period

John Wesley (1703-1791) and Charles Wesley (1707-1788)

John and Charles Wesley worked together in the rise of Methodism in the British Isles during the

18th century. They were among the ten children surviving infancy born to Samuel Wesley (1662 -

1735), Anglican rector of Epworth, Lincolnshire, and Susanna Annesley Wesley, daughter of

Samuel Annesley, a "dissenting" minister. John Wesley's mother was important in his emotional

and educational development. His education continued at Oxford, where he studied at Christ

Church and was elected (1726) fellow of Lincoln College. He was ordained in 1728.

After a brief absence (1727-29) to help his father at Epworth, he returned to Oxford. His

brother Charles had (in 1729) founded a Holy Club composed of young men interested in spiritual

growth. John became a leading participant of this group, dubbed the Methodists by other

students. His Oxford days introduced him not only to classical literature and philosophy but also

to works like Thomas a Kempis' Imitation of Christ, Jeremy Taylor's Holy Living and Dying, and

William Law's Serious Call.

In 1735 both Wesleys accompanied James Oglethorpe to the new colony of Georgia, where John's

attempts to apply his High-Church views aroused hostility. Discouraged, he returned (1737) to

England; he was rescued from this discouragement by the influence of the Moravian preacher

Peter Boehler. He began to realise that religion alone was not enough, and that his new friends

had a personal faith in Christ as their Saviour that he did not. At a small religious meeting in

Aldersgate Street, London, on 24 May 1738, Wesley had an experience in which his "heart was

strangely warmed. I felt that I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation; and an assurance

was given me, that He had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin

and death" In its context, this amounted to the time of his true conversion to Christ, which

centred on the realization of salvation by faith in Christ alone; he then devoted his life to

evangelism. Because of his evangelical preaching many churches barred him their pulpits.

Beginning in 1739 he established Methodist societies throughout the country.

From the start, the Methodists were concerned with personal holiness and emphasized the need

for an experience of salvation. To that end, they were involved in the earliest Sunday Schools,

and the first church publishing house in America was formed by them in 1789.

The Methodists were an integral part of the Second Great Awakening (1790-1840) and made

great use of revival meetings and camp meetings to call people to Christ. The concept of

circuit-riding preachers was developed by the Methodists and was used in frontier areas.

A preacher would be responsible to travel from settlement to settlement, preaching and serving

the people there until there was a large enough body to call a full-time pastor. The Methodist

Church follows general Wesleyan theology: belief in the sinfulness of man, the holiness of God,

the deity of Jesus Christ, and the literal death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus for salvation.

Wesley travelled and preached constantly, especially in the London-Bristol-Newcastle area, with

frequent trips into Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. He initially encountered considerable

opposition, which later subsided. He died at 88, still preaching, traveling, and a clergyman of

the Church of England. In 1784, however, he had given the Methodist societies a legal

constitution, and in the same year he ordained Thomas Coke for ministry in the United States;

this action signalled an independent course for Methodism.

Charles Wesley quickly earned admiration for his ability to capture universal Christian

experience in verse, often sung using popular tunes of the day. His hymns (many of which are

still sung) include: "And can it be", "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing", "O for a Thousand Tongues

to Sing", and "Love Divine, All Loves Excelling".

Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758)

Christian preacher and theologian. Edwards is widely acknowledged to be America's most

important and original philosophical theologian, and one of America's greatest intellectuals.

As a young man, Edwards was unable to accept the Calvinist sovereignty of God. He wrote,

"From my childhood up my mind had been full of objections against the doctrine of God's

sovereignty. It used to appear like a horrible doctrine to me". However, in 1721 he changed his

views. Meditating on 1 Timothy 1:17, he observed, "As I read the words, there came into my

soul, and was as it were diffused through it, a sense of the glory of the Divine Being; a new

sense, quite different from any thing I ever experienced before... I thought with myself, how

excellent a Being that was, and how happy I should be, if I might enjoy that God, and be rapt up

to him in heaven; and be as it were swallowed up in him forever!" From then on, he preached

the sovereignty of God. Edwards later recognized this moment as his conversion to Christ.

In 1727 he was ordained a minister at Northampton, assisting his grandfather, Solomon Stoddard.

However, Stoddard died on February 11th, 1729, leaving to his grandson responsibility for one of

the largest and wealthiest congregations in the colonies. Throughout his time in Northampton

his preaching brought remarkable religious revivals. Edwards was a key figure in what has come

to be called the First Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s.

Tensions flamed as Edwards would not continue his grandfather's practice of open communion.

Stoddard believed that communion was a "converting ordinance." Edwards became convinced

that this was incorrect, his rejection of the doctrine resulted in his dismissal in 1750. He then

moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, a frontier settlement, where he ministered to a small

congregation and served as missionary to the Housatonic Indians. Having more time for study

and writing, he wrote what became a celebrated work, The Freedom of the Will (1754).

Edwards was elected president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) in early

1758. He was a popular choice, for he had been a friend of the College since its inception and

was the most eminent American philosopher-theologian of his time. On March 22, 1758, he died

of fever at the age of fifty-four following experimental inoculation for smallpox and was buried

in the President's Lot in the Princeton cemetery beside his son-in-law, Aaron Burr.

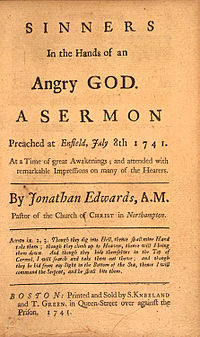

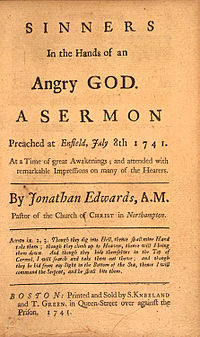

Edwards rejected much of the Puritan tradition and called for unity amongst all Christians. His

most famous sermon was "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God," delivered in 1741. In this

message he explained that salvation was a direct result from God and could not be attained by

human works as the Puritans preached.

British preacher, Dr. Martin Lloyd-Jones, said of Edwards: No man is more relevant to the

present condition of Christianity than Jonathan Edwards. He was a mighty theologian and a

great evangelist at the same time... he was preeminently the theologian of revival. If you want

to know anything about true revival, Edwards is the man to consult." Edwards continues to

influence American Christian leaders, eg Dr Timothy Keller, founding pastor of Redeemer

Presbyterian Church in New York City.

An investigation was made of 1,394 known descendants of Jonathan Edwards. 13 became

college presidents, 65 college professors, 3 United States senators, 30 judges, 100 lawyers, 60

physicians, 75 army and navy officers, 100 preachers and missionaries, 60 authors of

prominence, one a vice-president of the United States, 80 became public officials in other

capacities, 295 college graduates, among whom were governors of states and ministers to

foreign countries.

The Great Awakening

The Great Awakening was a period of revival that spread throughout the American colonies in

the 1730s and 1740s. It rejected baptismal regeneration (ie being born again through infant

baptism) emphasized individuals and their spiritual experiences. It came at a time when men

and women in Europe and the American colonies were questioning the role of the individual in

religion and society. It began at the same time as the Enlightenment which emphasized logic

and reason and stressed the power of the individual to understand the universe based on

scientific laws. Similarly, individuals grew to rely more on a personal approach to salvation than

church dogma and doctrine.

Under the preaching of Jonathan Edwards, revival came to Northampton (USA) in 1735, and over

300 converts were added to the church. Edwards recognized this was the work of the Holy

Spirit, for only God could convert a sinful heart and transform lives of self-seeking into lives of

Christian holiness. He shared the stories of the revival with correspondents in America and

England, publishing A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in 1737. This was only

the beginning; the revival spread quickly and many were converted to Christ.

When the English evangelist George Whitefield travelled throughout the American colonies in

1740-1741, revival swept through the colonies, bringing a "Great Awakening" to many. Edwards'

preaching in Northampton and surrounding churches continued to call people to recognize their

sinful condition and seek the Lord. Many were affected by Edwards' preaching. Some cried out

or wept in fear as they thought of the eternity awaiting them without Christ.

The move stressed individual experience over church doctrine, decreasing the importance and

weight of the clergy and the church in many instances. New denominations arose or grew in

numbers as a result of the emphasis on individual faith and salvation. It unified the American

colonies as it spread. It did not form around a complex theology of religious freedom, but

nevertheless the ideas it produced opposed the notion of a single truth or a single church. As

preachers visited town after town, sects began to break off larger churches and a multitude of

Protestant denominations sprouted. Older groups that had dominated the early colonies - the

Puritans and the Anglicans - eventually began a drastic downward trend in popularity.

The effect of Great Awakening unity was an attitude that went against the deferential thinking

that consumed English politics and religion. Rather than believing that God's will was

necessarily interpreted by the monarch or his bishops, the colonists viewed themselves as

capable of performing the task. The chain of authority no longer ran from God to ruler to

people, but from God to people to ruler. The children of revivalism later echoed this radicalism

and popular self-righteousness in the American Revolution, when self-assertion turned against

the ways of George III. Colonists were able to step out from under the protectorate of the

established Christian churches and assert religious control over their own nation's destiny.

George Whitefield (1714-1770)

English Anglican preacher who helped spread the Great Awakening in Britain and the British

North American colonies.

As a young man, Whitefield considered becoming a preacher and spent hours studying his Bible,

often reading late into the night. Shortly before entering Oxford, he was converted to faith in

Christ. While at Oxford, he met John and Charles Wesley, forming a friendship that God would

use on both sides of the Atlantic to influence multitudes with the Gospel. All three Englishmen

went to America in 1738. The movement known as the Great Awakening was just beginning, and

this was a time when God's Spirit moved across the nation.

When Europeans first came to the New World in the early 1600s, some were eager to share their

faith in Christ with the indigenous Americans. They desired to create a "shining city on a hill"

that would be an example to the rest of the fallen world, an idea that John Winthrop preached

about on his way to Massachusetts. Many were seeking a country where they could freely

practice their faith, unlike the nations from which they fled. By the early 1700s, traditional

churches had largely settled into self-satisfaction. Their preachers delivered dry sermons and

avoided speaking about winning souls to Christ. Under this kind of leadership, faith often

withered, lacking the vital spark that would make it relevant to their everyday lives.

Due to his preaching style, pulpits closed to Whitefield in many "respectable" English churches.

When this happened, he took his messages outside, often preaching in meadows at the edges of

cities. This was considered sacrilege to the "proper" church members of his day, but large

numbers of people alienated from the organised church were reached and thousands were

converted.

Whitefield joined other ministers like Jonathan Edwards, Gilbert Tennent, David Brainerd, and

the Wesley brothers to rekindle believers' faith in Christ. The revival of the Great Awakening

was an event in which all of the colonies shared, giving them a common, unifying experience.

Many believe that God used the Great Awakening to draw the American colonies into closer

union, preparing them for independence.

During his lifetime, Whitefield delivered over 18,000 sermons to an estimated ten million

people, averaging roughly ten sermons a week. This was extraordinary at a time when there

were no television or mass communication.

John Newton (1725-1807) - "Amazing Grace"

John Newton, an Englishman, was nurtured by a Christian mother who taught him the Bible at an

early age until she died prematurely. When he was 11, he went on his first of six sea-voyages

with the merchant navy captain.

He spent his later teen years at sea before being press-ganged (a form of conscription common

at the time) aboard the HMS Harwich in 1744. He rebelled against the discipline of the Royal

Navy and deserted. He was caught, put in irons, and flogged. He eventually convinced his

superiors to assign him to a slave ship. Newton took up employment with a slave-trader named

Clow, who owned a plantation on an island off of West Africa. But he was treated cruelly by

Clow and his African mistress; soon his clothes turned to rags, and he was forced to beg for food.

Newton was transferred to the Greyhound, a Liverpool ship. In 1747, on its homeward journey,

the ship was overtaken by an enormous storm. Newton had been reading Thomas a Kempis' The

Imitation of Christ, and was powerfully struck by a line about the "uncertain continuance of

life." He recalled the passage in Proverbs, "Because I have called and ye have refused, I also will

laugh at your calamity." (Proverbs 1:24-29). He gave his life to Christ during the storm.

Newton subsequently served as mate and then captain of several slave ships, hoping as a

Christian to restrain the excesses of the slave trade, "promoting the life of God in the soul" of

both his crew and his African cargo.

- Discussion: what do we think of this argument, in the context of the time?

After leaving the sea for an office job in 1755, Newton held Bible studies in his Liverpool home.

Influenced by both John and Charles Wesley and George Whitefield, he adopted mild Calvinist

views and turned his back on the slave trade. He was ordained into the Anglican ministry, and in

1764 took a parish in Olney, Buckinghamshire.

Three years after Newton arrived, poet William Cowper moved to Olney. Cowper, a skilled poet

who had experienced bouts of depression, became a helper in the small congregation. In 1769,

Newton began a Thursday evening prayer service. For almost every service, he wrote a hymn to

be sung to a familiar tune. Newton challenged Cowper also to do likewise, which he did until

falling seriously ill in 1773. Newton later combined 280 of his own hymns with 68 of Cowper's in

what was to become the popular Olney Hymns. Among the well-known hymns in it are "Amazing

Grace", "Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken," "How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds," "O for a

Closer Walk with God," and "There Is a Fountain Filled with Blood". Other famous hymn writers

of this period include Isaac Watts, "When I survey the wondrous cross" (1709).

William Wilberforce (1759-1833)

William Wilberforce was one of Britain's great politicians and social reformers. He is

remembered, in particular, for his active participation in getting Parliament to outlaw the slave

trade. He died in 1833, just three days before Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act 1833,

which effectively banned slavery in the British Empire.

The movie, Amazing Grace (2007), from director, Michael Apted, tells the inspiring story of how

one man's passion and perseverance changed the world. Based on the-life story of Wilberforce,

the film chronicles his struggle to pass a law to end the slave trade in the late 18th century.

Along the way, Wilberforce meets opposition from members of Parliament who feel the slave

trade is tied to the stability of the British Empire. Several friends, including Wilberforce's

minister, John Newton, urged him to see the cause through.

Charles Finney (1792-1875)

A leader in the Second Great Awakening, Finney has been called "The Father of Modern

Revivalism". Finney studied law from 1818 to 1821, when he had a sudden conversion

experience. After this he began to preach and was licensed to preach by the Presbyterian

denomination in 1824. Wherever he travelled he started extensive religious revivals.

Finney was criticized because he emphasized the will of man in conversion and employed

techniques that became known as "New Measures", calculated to evoke emotional responses.

Impatient with Presbyterianism, he became a Congregationalist, serving New York City's

Broadway Tabernacle. Finney was appointed professor of theology at Oberlin College (1835),

minister of the First Congregational Church at Oberlin (1837), and was named president of the

college in 1852. His Lectures on Revivals (1835) became a handbook for American revivalists.

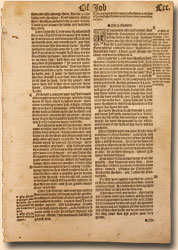

The King James Version of the Bible

Geneva Bible (1560)

Matthew-Tyndale Bible, 1549

King James Version

In 1604, King James I of England authorized that a new translation of the Bible into English be

started. It was finished in 1611, just 85 years after the first translation of the New Testament

into English appeared (Tyndale, 1526). The Authorized Version, or King James Version, quickly

became the standard for English-speaking Protestants. While fewer people read the KJV today, in

comparison with other versions, its flowing language and prose rhythm has had a profound

influence on English language literature during the past 400 years.

- What do we think about different versions of the Bible? Should they be called

"translations"? Is this diversity trustworthy?

Languages change, so it is important that the Word of God be in a version we can understand.

Consider the following extract from Canterbury Tales, written in English:

He was an esy man to yeve penaunce,

Ther as he wiste to have a good pitaunce.

For unto a povre ordre for to yive

Is signe that a man is wel yshryve;

For if he yaf, he dorste make avaunt,

He wiste that a man was repentaunt;

For many a man so hard is of his herte,

He may nat wepe, althogh hym soore smerte.

Therfore in stede of wepynge and preyeres

Men moote yeve silver to the povre frères

The Westminster Confession of Faith

A comprehensive statement of faith. It is possibly the greatest of all the creeds of the Christian

Church. Since its first publication in 1646 it has remained absolutely unsurpassed as an accurate

and concise statement of Christian doctrine. Among all the shifting sands of theological opinion

here is solid truth, for it has its foundation in the unchanging truth of Scripture--witness the

copious references from the Bible which are printed on each page. Because of its faithfulness to

Scripture the Confession has permanent worth and abiding relevance.

The 18th Century Awakening: What we can learn from it

By Editorial Staff

Published December 1992

Evangelicals in the United States today feel frustrated because they have failed to transform

American society in recent years. English and American evangelicals in 1730 felt much the same

way. Many years of political and social effort had not succeeded in bringing reform. Yet within a

decade they experienced what is now called "The Great Awakening", during which time their

nations' political and social cultures were radically impacted by Christian values. The following

ten characteristics of the revivals that took place in America, England and Europe are instructive:

1. Prayer. Evangelicals in the 1700s learned that corporate prayer was a prerequisite for

outpourings of God's Spirit. The revivals in many places were preceded by days of prayer and

fasting. Jonathan Edwards believed that corporate prayer was more effective than just the

combined prayers of individuals.

2. Leadership. God raised up strong leaders to guide the movement. Jonathan Edwards was the

theologian of the awakenings and his writings were a powerful influence even until the end of the

following century. George Whitefield was a dramatic and powerful orator, able to deeply move

audiences with his sermons. John Wesley was an administrative genius who established an

extremely effective small-group structure of class meetings which kept the revival fires burning.

3. Doctrine. Revival preachers of the time focused on the great Reformation doctrines of

justification by faith and the atonement. They emphasized God's judgment and then his grace.

4. Emotionalism. The revivalists unashamedly appealed to people's emotions. They felt that their

listeners' problem was not a lack of knowledge but a need to take action. They abandoned the

formality of manuscripts or notes and preached as the Spirit led.

5. Music. As one aspect of that emotionalism, evangelicals noted that music was an effective way

to stir religious affectations and they made frequent use of it.

6. Open-air meetings. Whitefield preached in open spaces where large crowds could gather.

Wesley took the message to jails, inns and ships, as well as outdoors.

7. Persecution. At times these preachers faced fierce opposition from hecklers, gangs of attackers

and the press.

8. Testimonies. Reports of revival in other places often sparked new outbreaks as lay people who

had been there first shared firsthand accounts of what the Holy Spirit was doing.

9. Holy Spirit. The 18th-century revivalists expected the Spirit to manifest His presence in

powerful, visible ways.

10. Social action. A greater concern for the poor and downtrodden often resulted from these

revivals. Jonathan Edwards taught that it was the Christian's duty to be charitable. Whitefield

devoted a great deal of his energy to an orphanage he founded in Georgia.

The conclusion can be drawn from the 18th-century experience that a deep and powerful spiritual

renewal can be more effective in transforming a culture than political action.

Gerald McDermott, National & International Report, Dec. 14, 1992

(http://www.sermonindex.net/modules/newbb/viewtopic.php?topic_id=30537&forum=40)

Issues

- What do we understand by revival? Is there a "theology of revival?"

- restoration of basics: relationship with God, prayer, dynamic Word of God

- freshness in worship

- Christocentric Christianity

- passion for reaching the lost; harvest, church planting, mission, church growth

- simplicity, unencumbered by human tradition

- anointed preaching

- demonstrations of the presence and power of God

- emphasis on repentance, holiness (without legalism),

- What were the hallmarks, fruits of genuine revival during the Great Awakening?

Additional Reading

Blainey, G, A Short History of Christianity, Viking, Melbourne, 2011

Bragg, M, The Book of Books: The Radical Impact of the King James Bible 1611-2011, Sceptre, London, 2011

Bunyan, J, The Pilgrim's Progress: From this World to that which is to come delivered under the similitude of a dream, Lutterworth Press, London, 1961 Edition

Lindsay, K, Civil War in England, Frederick Muller, London, 1954

Lion, A Lion Handbook, 1990, The History of Christianity

Miller, A, Miller's Church History: From the First to the Twentieth Century

Miller, B, Charles Finney, Dimension Books, Minnesota, 1941

Renwick, AM, The Story of the Church, Intervarsity Press, Edinburgh, 1973

Brother Lawrence, The Practice of the Presence of God, Paris, 1666, various publishers, including Wilder Publications, Radford, 2008

Leonard Ravenhill, Why Revival Tarries, Baker, 1959, and other works

Wilberforce, W, Real Christianity, Ed by Dr Vincent Edmunds, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1989 (first published 1787)

In September 1620, a merchant ship called the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth, a port on the

southern coast of England. On this trip the ship carried 102 passengers, all hoping to start a new

life on the other side of the Atlantic. Nearly 40 of these passengers were Protestant Separatists-

they called themselves "Saints"-who hoped to establish a new church in the New World. Today,

we often refer to the colonists who crossed the Atlantic on the Mayflower as "Pilgrims." The

Puritans believed the Bible was God's law, and that it provided a plan for living. The established

church limited access to God to the confines of "church authority". Puritans sought to strip away

traditional trappings and formalities of Christianity that had been slowly building.

In September 1620, a merchant ship called the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth, a port on the

southern coast of England. On this trip the ship carried 102 passengers, all hoping to start a new

life on the other side of the Atlantic. Nearly 40 of these passengers were Protestant Separatists-

they called themselves "Saints"-who hoped to establish a new church in the New World. Today,

we often refer to the colonists who crossed the Atlantic on the Mayflower as "Pilgrims." The

Puritans believed the Bible was God's law, and that it provided a plan for living. The established

church limited access to God to the confines of "church authority". Puritans sought to strip away

traditional trappings and formalities of Christianity that had been slowly building.